October 23, 2017

Wall Street Journal

Will sports be able to survive robot referees and biomedical player monitors?

Forget fall foliage. I know only three seasons—baseball, basketball and football—and for the next week or so they coexist. They bring with them virtual strike zones, on-field stats, rotating 360-degree views, and yellow first-down lines. Technology has changed sports—but not always as intended.

Green Bay Packers return specialist Desmond Howard admitted after his 99-yard kickoff return in the 1997 Super Bowl that he’d had a technological assist: “You can use the jumbotron almost like a rearview mirror, and so that’s what I did.” Twenty years later, the Boston Red Sox got caught stealing Yankee catchers’ signs, relayed to the dugout via an Apple Watch. At least someone found a real use for the device. These examples are nothing compared with the benefits to fans from all the gizmos packed into stadiums and arenas. From pylon-cams to sensors capturing launch angles and exit velocities, the games are wired.

Gerard J. Hall runs SMT, a North Carolina-based company that provides broadcasters with much of the tech that enhances the viewing experience. He told me that “baseball actually uses our technology to train umpires.” To display an ESPN K-zone, every pitch is tracked for speed, location and path, and run through algorithmic filtering for accuracy. If you watch enough baseball, you know it’s way more accurate than human umpires. Will this technology replace the ump? “Assuming people want to get it right, it’s available,” says Mr. Hall.

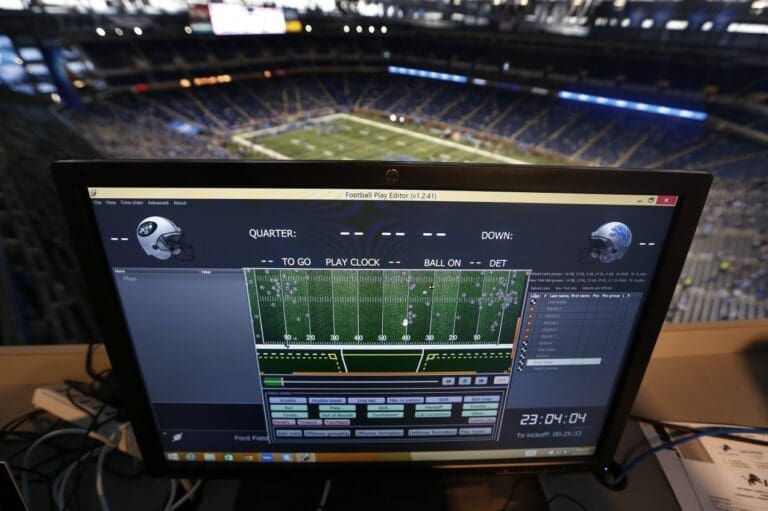

Since 2015, the National Football League has placed chips under shoulder pads to track exactly where players move. Fans can’t get this data, but teams can. Mr. Hall tells me it can provide “instant analysis to coaches.” Real-time analytics and machine learning might someday even call for specific plays, like former coach Jon Gruden’s “Spider 2 Y Banana,” in certain scenarios. SMT is also working with Duke football on a system called Oasis, which will use biomedical sensors to track players’ heart rates, body temperatures and hydration—as if they’re astronauts.

So many of the changes in sports rules have been to attract fans and jam in more Chevy Silverado and Dr Pepper commercials. In football, illegal contact and downfield chuck regulations from 1994 favor quarterbacks and receivers, who run up scores. The National Basketball Association’s 3-point line, added in 1979, and its 2001 defensive three-second rule also favor offenses and more points. Even baseball has been accused of juicing the balls and lowered the pitching mound from 15 inches to 10 inches in 1969. More runs, more razors sold—up to a point.

I’m a techno-optimist, but even I can see the downside. With commercials and replay challenges, games have become painfully long. In the 1960s and ’70s, the Cardinals’ Bob Gibson pitched wins in under two hours. A Cubs-Nationals playoff game this month lasted 4 hours and 37 minutes. Long games also contribute to the NFL’s ratings problem, which began before the national anthem protests. Many fans care more about fantasy-football stats for individual players than about which team wins. “NFL players,” Mr. Hall says, “have become the random-number generators for people’s fantasy-football games.”

Dugouts are filled with binders of statistics, and Microsoft tablets regularly appear on the NFL’s sidelines. Both are used to track the opposition’s tendencies and enable player shifts. I like this in my business strategy but maybe not on a field of play. As Hall of Fame quarterback Steve Young once told me, football is now so choreographed, it’s almost like the ballet.

Something has been lost. Indoor arenas and artificial turf have their benefits, but I miss the days of mud bowls, where you couldn’t read the players’ numbers or even make out the field’s hash marks. I miss the pitcher who could own home plate with a brushback pitch, affectionately known as “chin music.” I miss big sweaty bruiser centers brawling under the hoop. As Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s character in “Airplane” famously complained: “Tell your old man to drag Walton and Lanier up and down the court for 48 minutes!”

Where is all this headed? Mr. Hall says SMT will quite soon have the ability to “3-D model every arena, and not only track every object on the field, but create a 3-D video overlay.” Think “ Madden NFL 18,” not “Monday Night Football.” When Generation Twitch sees this, they won’t be reaching for remotes, they’ll be grabbing Xbox controllers and wanting to take charge.

Right now, millions of people regularly watch others play videogames online. It’s a real phenomenon. There are more than 30 e-sport tournaments and leagues, where caffeine is a bigger problem than steroids. Ponder this: The League of Legends world championship finals—perhaps the most prestigious event in e-sports—attracted 43 million unique viewers. That’s more than the NBA Finals.

Are live sports doomed by techno-perfection? Mr. Hall doesn’t think so. “It’s still humans playing a game,” he says. “There’s too much human frailty, and human genius, to take the soul out of the games.” Probably so, but it may not move a lot of Bud Light.

Mr. Kessler writes on technology and markets for the Journal.