July 11, 2017

Wired

IT’S THE NIGHT before the world’s first professional flag football game, and everything’s going wrong. Not that it matters.

The league’s two teams, led by former NFL all-pros Mike Vick and Terrell Owens, have just taken the field for a dress rehearsal of sorts. On the first play, someone bobbles the throw-off. (Throw-off? Yes. There’s no kicking in flag football.) That should end the play, but no one remembers that. The 14 players on the field keep at it until Jeffrey Lewis, the founder of the American Flag Football League, runs toward the field yelling “Dead! Dead! Whistle!”

Not to worry. Everyone will figure out the rules. The flags pose a bigger problem. They use magnets and wireless radios to help referees pinpoint exactly where a ballcarrier went down. But the magnets won’t hold through the vinyl on the flag, and Velcro can’t stand up to the rigors of gameplay. League employees pace the sidelines here at Avaya Stadium in San Jose, debating a solution. Maybe Gorilla Glue?

Still, Lewis seems pleased. He summons two people to a monitor propped up in the midfield tunnel to explain why. Chaos reigns on the field, but the broadcast feed looks gorgeous. The virtual first-down line holds in place. The swooping SkyCam looks almost Madden-like. The “Go Clock” that counts down the four seconds until the quarterback must pass or run works perfectly. Replays come from all angles just moments after each play. And with no helmets or pads in the way, viewers can see every grimace, every celebration, and frustrated harumph. It makes for great TV, which is all that really matters to Lewis.

Lewis and his team spent just nine months building the AFFL: lining up investments, writing the rules, finding players and broadcasters and live-streaming partners. So far, the league consists of just two teams and the goal of launching the Flag Football US Open next year. This isn’t the first league to challenge the supremacy of the NFL, but Lewis believes flag football provides a faster, safer, more social media-savvy take on football. He’s definitely on to something. Now if the players could just remember the rules.

Redesigning the Gridiron

The way Lewis tells it, the AFFL started on the sidelines of his son Hayden’s flag football game. He’d coached the game for a few years, and found the sport surprisingly entertaining. “It just made me say to myself, ‘I wonder what this game would look like if it was played by the greatest players in the world?'” he says. He figured he could tap the pool of skilled players who aren’t in the NFL for one reason or another and create a league just as exciting.

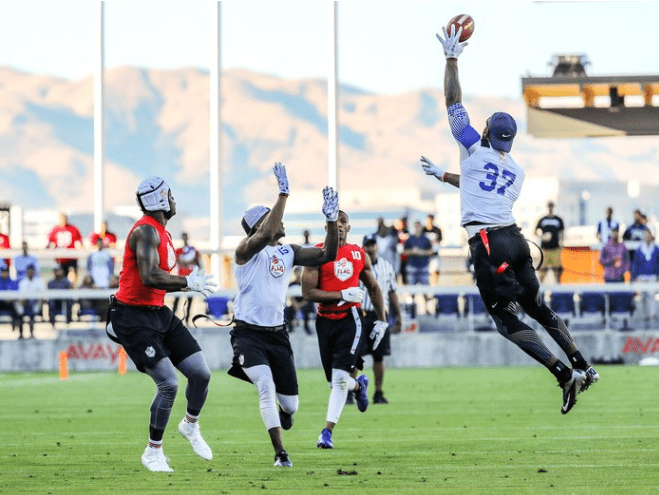

The game riffs on the one you probably played as a kid. Players spend 60 minutes working their way up and down a standard football field delineated by four 25-yard zones. Each team features a dozen players and fields seven at a time. Everyone plays offense and defense. Games start with a throw-off, with a player of the coach’s choice hurling the ball as far as possible. The receiving team has four plays to reach the next 25-yard zone, then the next, and so on until it scores or throw-punts (no kicking, remember?). The game moves quickly—the quarterback has just four seconds to heave the ball or start running, and the defense can rush the backfield after two seconds. Someone pulls your flag? You’re down.

Touchdowns from less than 50 yards earn six points. Anything longer earns seven. After scoring a touchdown, teams can go for one, two, or three more points with a conversion. Tackling, blocking, and kicking? Strictly forbidden. The clock runs constantly, until the last two minutes of the first half and the last five of the second half, when the clock stops after each play.

The league launches next year with the Flag Football US Open, an epic tournament that Lewis envisions drawing 1,000 teams and a seven-figure prize. Winning teams will recruit from losing teams, until only the best remain. Think of of it as American Idol or American Ninja Warrior, but with a football. The eight best teams will then play the inaugural AFFL season.

To pull this off, Lewis hit up friends, family and investors. Everyone called him crazy. They pointed to the long list of wannabes that hoped to challenge the NFL. Remember the XFL? Ever watched arena football? The United Football League lasted all of four seasons (go Destroyers), and even the NFL’s European expansion flopped. The NFL has many problems, but disruption is not one of them.

When I point this out, Lewis waves me off. Those leagues couldn’t execute, he says. You can see his point. The XFL debuted to enormous ratings in 2001 but quickly fell apart because no one wants wants football with wrestling. Every challenger failed because they offered, well, crap. “It would be like, ‘Oh, it’s the same game as the pros, with people who aren’t as good,” says Darren Rovell, a sports business reporter at ESPN. People do want more football, Rovell says, but the game must offer something novel.

The novelty of flag football, of course, contains something at least one potential investor considered a downside: the complete lack of violence. “He felt the violence of football was the primal element, that it was what drew people to football,” Lewis says. Eager to prove the naysayers wrong, Lewis and his team scoured social media data, trying to figure out what people talk about while watching NFL games. Turns out words like touchdown, pass, run, and interception come up a lot. Hit, block, and tackle? Not so much. The NFL offers the Red Zone channel to show non-stop scoring, but as Lewis says, “there’s no Hard Hits channel.” If social media is any indication, then you’ll find all of the most exciting and shareable parts of the NFL in flag football.

The more Lewis researched, the more opportunity he saw on social media. For instance: Football remains America’s most popular sport, yet no NFL players appear in top 20 of ESPN’s list of the 100 most famous athletes. Only Tom Brady (No. 21) and Cam Newton (No. 47) crack the top 50. Lewis firmly believes that’s because NFL players are faceless gladiators that viewers can’t relate to. In other sports, “whether you’re rooting for a guy or against the guy, he’s a character, and you feel like you have a relationship to them,” Lewis says. Eliminating the helmets and pads makes it easier for viewers to see, and relate to, players. And the AFFL wants those players tweeting, streaming, snapping, and posting nonstop—things that’ll earn you a fat fine in the NFL—to deepen their relationships with fans.

Prototype Pigskin

With no players union to fight, billion-dollar TV contracts to protect, or traditions to uphold, the AFFL has been free to use technology in novel ways to enhance the game.

Take the flags: Refs must know exactly where a player is when his flag gets pulled. This is trickier than you think when you’ve got 14 guys hustling through a play. The flag might flutter away, or be thrown aside by the guy who yanked it. So the league tapped SMT, the company that invented the virtual first-down line and handles scoring and statistics for the NCAA basketball tourney, the Super Bowl, and Stanley Cup. SMT developed a simple vinyl flag with a magnet sewn into one end that sticks to another magnet on a belt around the player’s waist. Separate the magnets and a sensor in the belt sends a signal to a small transmitter on each player’s shoulder. That transmitter communicates constantly with wide-band wireless receivers, suspended from the stadium’s ceiling, that record every player’s location 15 times per second. By matching the detach signal to a location on the field, SMT’s system can pinpoint to within 3 inches where a flag was pulled. The system’s not just for players, by the way: A sensor in the ball provides incontrovertible proof of whether the quarterback threw the pass in time.

The technology ensures officiating accuracy which, combined with subtle tweaks to the rules of football, makes for snappier gameplay. There will be no interminable four-hour games riddled with eight-minute replay reviews; Lewis wants to see games last two hours and not one minute more. Refs in the review booths way up in the press box will leave most calls to their colleagues on the field, but if someone gets something wrong, the computers will know almost immediately.

The flag-pulling stuff is nothing compared to Oasis, SMT’s sophisticated system for tracking a player’s heart rate, temperature, speed, impact force, and other data in real time. “The idea that you get that stuff live is a damn big deal,” says company CEO Gerard J Hall. All that data can help protect players, and help them optimize their performance. Hall says he’s talking to the AFFL about doing more with the system.

It’s worth noting that football without tackles is a far safer game, one that greatly diminishes the risk of concussions and CTE. But Lewis sidesteps the idea that part of the appeal here is “the NFL, only safer.” If nothing else, safety makes for a boring marketing plan. Yet he can’t have missed the growing trepidation, if not moral ambivalence, fans feel as the game’s dangers become more widely known. Just as the XFL pioneered on-field interviews and the SkyCam, the AFFL could show the potential of tracking player data on the field. If nothing else, it gives Lewis and Hall a backup plan. “That business [Lewis] says he has,” Rovell asks, referring the league itself, “is that really the business? Or is that just a red herring? Is he going to sell the tech to the NFL, which is bigger than any flag football league could ever be?”

Going Live

The day after that haphazard scrimmage, which saw those magnets replaced with Velcro and a long night of production meetings, the AFFL made its first big show. A few hundred fans filed into the stadium, each grabbing a brochure announcing the AFFL and explaining the rules of the game. Some wanted to see a game they know from childhood played at the highest level. Others held loftier goals. “I might try to get on the field,” one slightly drunk observer told me. “We’ll see.” But mostly people wanted to see the likes of Vick and Owens playing again.

The two rosters combined veterans of the 2003 Pro Bowl and guys who almost made it in the NFL. Vick, Owens, and Chad Ochocinco were among the sport’s brightest stars during their illustrious (and controversial) careers. Justin Forsett, Jimmy Clausen, and Jonas Gray played one or two great games before moving on. And guys like Najee Lovett, Yamen Sanders, and Stephen Godbolt never saw a pro gridiron. Some of them consider the AFFL a stepping stone to the NFL. Others seem to simply enjoy playing again. And they share a common motivator: Appearing the inaugural game earned them equity in the league. Players on the winning team earn even more shares.

The success of the league depends upon the celebrities it can create. And so about 10 minutes before throw-off, fans gathered at the tunnel as players trickled onto the field for autographs and selfies. After mingling with fans, the players hit the field, hooting and hollering and snapping photos of their own.

The two-hour game went more smoothly than the dress rehearsal, with plenty of circus catches, more than 100 points scored, and Vick doing cartwheels. Players ran three-point conversions and seven-point touchdowns. The final play was a pick-six onside throw-off, run back for a touchdown by Max Siebald, a former lacrosse player. None of which makes any sense, but all of which somehow felt appropriate.

Vick’s team won, 64-41. A few minutes after the game ended, the players gathered on the sidelines. Evan Rodriguez, a brawny former NFL tight end who caught four touchdown passes and was named the game’s MVP, gathered his teammates behind him. He raised his gold iPhone high overhead in his left hand, and everyone grinned and shouted and threw their arms up. Rodriguez snapped a selfie. At that moment, the AFFL was truly born.