By Joe Lemire | SportTechie

NEWARK — High up above the ice at the New Jersey Devils’ Prudential Center, 16 small silver boxes have been affixed to the rafters. Each is adorned with a large yellow sticker featuring all-caps letters in bold: NOT A STEP. A crossed-out shoe print punctuates that command. A pair of antennas flank both sides of the boxes, which house infrared cameras and have protruding lenses pointing down toward the rink 110 feet below.

On the ice, nearly two dozen NHL employees—with a wide range of hockey ability—are preparing for a friendly scrimmage. Equipment managers slip small electronic devices, about the size of a boxcutter, into pouches between the shoulder blades on the back of every player’s jersey. Every puck also features a microchip embedded in its core, with six light emitters on the top and six more on the bottom, all painted black to hide their existence from all but the closest scrutiny.

On the catwalks, Keith Horstman, the NHL’s VP of technology, explained what was happening below as he gave SportTechie a behind-the-scenes tour of the league’s new tracking system. Developed by SMT, the technology is being installed in all 32 NHL arenas, including the two venues that the New York Islanders call home. During games, the central system will send out radio pings to the puck and player devices, which will reply by emitting pulses of infrared light. The infrared cameras can sense and triangulate those signals, locating the players and puck in three-dimensional space and transmitting that data nearly in real-time.

The puck and player tracking system aims to foster fan engagement by augmenting broadcasters’ storytelling capabilities, help team analysts unlock new insights, and aid player wellbeing through monitoring of in-game workloads. The legalization of sports betting during the project’s six-year development timeline added a bonus fourth use case.

On the night that Horstman showed SportTechie around, NBC and SMT employees were in Newark for a dry run of the upcoming NHL All-Star Game broadcast (the actual game will be played in St. Louis). The employee scrimmage, which was just a way to test the system, was often interrupted by the crackle of radios signaling requests from the TV production crew asking for specific scenarios: a 5-on-3 power play and a hardest shot competition, which in this instance topped out at 76 mph—about 30 mph slower than the top NHL slap shots.

This year’s NHL All-Star Game will be the second-straight year the league’s midseason exhibition will feature tracking technology. The league signed a deal with German startup Jogmo early last January to supply its tracking system and ran a test during the 2019 All-Star Game. But the NHL abruptly shifted course at the beginning of the 2019-20 season, switching to SMT, an industry veteran based in Durham, N.C., that also provides the league’s official scoring system.

On Saturday, NBC in the U.S. and Rogers-owned Sportsnet in Canada will incorporate some tracking data in their linear broadcasts. NBC will also produce a separate digital broadcast—available via the NBC Sports website and app—that will be primarily focused on leveraging the data. The league’s plan is to follow the All-Star Game with several regular season showcases of the technology—two games in Toronto, two others in Washington—before its fully deployed in the postseason. The goal is to have the data highlight aspects of the game that might otherwise be difficult to see.

“You can see the beauty of these guys,” Hortsman says. “From my perspective, the game is really about passing. And to be able to see the passing lanes and see how these guys thread a three-inch puck in a window that’s four inches wide is just mind-boggling.”

* * * * *

Since the league made the switch to SMT in October, four work crews have been traveling to every NHL arena around North America. The first team’s role is to survey the venue and, with the help of the arena’s operator, determine optimal locations for every infrared camera. A cable contractor will then lay down new wiring to connect the cameras, and then one of the other three crews will install and test the hardware.

Calibration requires methodically introducing the infrared-emitting tags to the ice to slowly construct a map of the surface and then challenge the system with tracking movement. First, SMT will position tags in specific locations—face-off dots, blue lines, the center red line and goal lines—so that its computers can record where those are in space. (The infrared cameras cannot otherwise see those features.) Next, someone will skate around the ice while wearing a tag to fill in the horizontal x-y coordinates. Then the skater will take a camera tripod out onto the ice, with tags affixed to its top, middle, and bottom to add vertical z coordinates to the system. Only then will pucks finally be introduced, with skaters firing as hard and high as they can.

There’s no worry about infrared signals being blocked by other skaters or objects in the arena because the cameras are positioned so high up (and because there are so many of them; arenas average between 14 and 18 cameras). Early trials discovered a need for more coverage of action behind the goalie, which was remedied by adjusting camera placements. Some female players were also hard to track because their ponytails hung down over the tags and occluded the signals, prompting the league to relocate some tags slightly off-center.

To test the system during game days, Horstman says the NHL has so far placed tags on everything except players—Zambonis, ice shovels. The speed of each was corroborated with a handheld radar gun. (The Zamboni’s speed: not fast.) The communications and tracking have so far held up to stress tests. “It’s nice to be able to sleep at night,” Hortsman sayd. “We’ve successfully had the [tags], though not in the game, out on the ice with fans and everything else in the venue.”

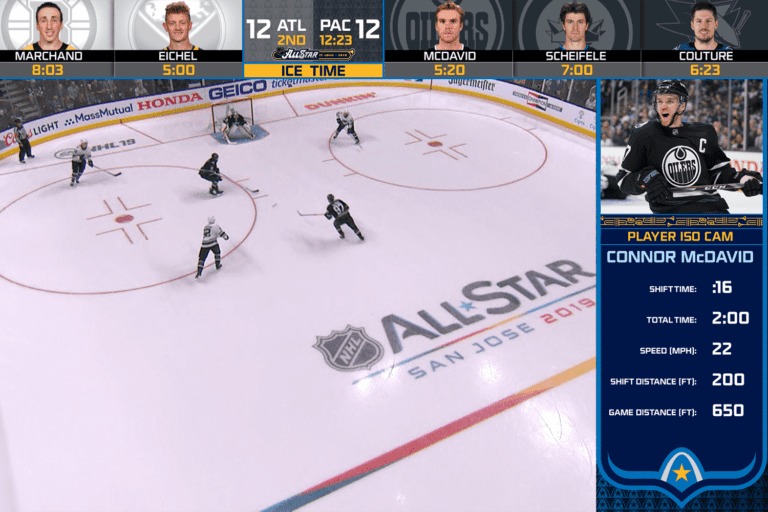

For the employee scrimmage at the Prudential Center, Horstman scripted a basic algorithm to identify and report shot data. Eventually, sophisticated machine learning will help categorize passes, dump-ins, breakaways and every type of action. For now, the metrics will be relatively simple. NBC’s All-Star Game coverage will include similar data to last year—player and shot speeds, as well as shift lengths—but the presentation of that information has been refined.

“You’re still going to see plenty of the metrics and ice time [data] and all that, but there’s going to be a little less clutter on-screen than there was last year,” says NBC Sports producer Steve Greenberg, who’s overseeing the digital feed.

* * * * *

In a side room on the Prudential Center’s basement-level concourse, NBC and SMT producers brainstormed ideas and discussed future use cases. Among the early renderings was what they called the “polygon,” a series of lines connecting the on-ice players to show their distance of separation. Such info could eventually inform analysis on how well sharpshooters such as the Washington Capitals’ Alexander Ovechkin or the Boston Bruins’ David Pastrnak draw defenders away from teammates or what the ideal spacing on a 1-3-1 power play might be.

The system will record the puck’s location 60 times per second, and each player’s position 15 times per second. Analysts and trainers may crave the raw data produced, but fans are going to need context and graphics, in as close to real-time as possible.

“You can have a bunch of Ph.D. scientists and spreadsheets spew out a particular piece of data, but when you can show that data visually, man, does that just change the whole world,” says SMT founder and CEO Gerard J. Hall.

All of the data collected from the ice, from advanced tracking info to referee whistles that stop the clock, is fed into SMT’s OASIS (Organization of Asynchronous Sports Information Subsystems) platform. Within OASIS is an AI engine called EIEIO, which technically stands for Eventing Intelligence Engine Inside Oasis, but sounds very much like the refrain from Old MacDonald Had a Farm. (“We’re very cute with our acronyms,” Hall quips.)

EIEIO will power the insights that the hockey industry is so excited to see. “We can infer all sorts of other data that humans just can’t do quick enough,” Hall says. “We can write computer algorithms and machine learning to drive other things—like in hockey, for example, there’s never been a live possession indicator. Who’s actually in possession of the puck? Because how would a human possibly be able to move fast enough to get that information?”

The tracking system’s potential is significant, not only to create more advanced stats—the league is also working with Sportlogiq to develop an optical tracking system to complement the puck and player tracking—but also to optimize existing workflows. “We will be able to create our statistics more accurately and faster,” Horstman says.

Broadcasters will benefit from both new insights and the ability to streamline production. Horstman believes tracking player behavior could help automate replays. “If you’ve got five guys on the same team come together and they go to the bench and high-five each other, you can derive that that was a goal and do something in your app,” he explains.

Adds Hall, “The EIEIO engine knows who the shooter was. It knows the distance skated and knows who the assist was and knows the pattern of everything [that] happened prior to the goal being scored. So we immediately, instantly create [a replay]. And we know when, for example, the puck came into the zone, we know the moment the goal was scored, so we can automatically clip off a segment of video.”

Knowledge is power, and the tracking information will surely be leveraged to create innovative AR and VR graphics, gaming apps and other applications that may change the way fans, players and coaches watch and understand the game of hockey. The NHL is sharing some of that data with a select group of third-party developers to create products for the showcase games. In Newark, a few of those developers sat on a sideline bench, watching the scrimmage and awaiting their chance to play.